If the eyes truly are the windows to the soul, don’t we want to see them when we ask someone to be thoughtful, frank, and honest? Don’t we want to look into their eyes — and have them look into ours — to see if they’re telling the truth?

When I’m shooting interviews on video or film, the subject often asks whether to look directly into the lens, or off to one side at the interviewer. Worst case is when he or she doesn’t know where to look and glances about wildly, desperately seeking eye contact and approval, and appearing to all the world like a shifty-eyed no-goodnik. This can cause even unsophisticated audiences to mistrust the person they’re watching.

Historically, most movies use an objective camera style, where actors in closeup look to one side of the camera. Having actors look directly into the lens — subjective camera style — can be extremely disarming. An early use of subjective camera occurred in the final shot of The Great Train Robbery, Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 film, where the bank robber, in closeup, pulls a gun and shoots directly at the camera, and thus at the viewers. This startling angle excited audiences at the time and has been reprised in the final scenes of Goodfellas and American Gangster.

Subjective camera has been a major cinematic device in the film noirs Dark Passage and Lady in the Lake, as well as countless point-of-view shots in horror movies and fight scenes over the decades, but by and large, objective camera still rules in the vast majority of films.

Television decided long ago to break the objective camera convention. Hosts, emcees, news anchors, pundits and reporters look directly at the lens, creating an instant rapport with viewers in their living rooms. TV professionals, unlike actors, are trained to talk directly to the audience. If news people have scripts, they read from a teleprompter mounted on the camera, a device invented in the 1950s to help Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz read commercials on their show I Love Lucy.

In interviews, however, the standard eyeline convention is to the side of the camera. In this traditional objective newsy look, the subject responds to questions from an off-camera, often-unseen interviewer.

I was once told by a news director at a local station that the subject should be looking “at 45 degrees to the axis between his face and the lens.” I tried to obey this dictum in my early years, but I thought this rule brought the eyeline too far to the side, and it seemed excessively doctrinaire: could the same angle be correct for everyone?

In my subsequent experience, I found most directors interested in bringing the eyeline closer to the camera. Interviewers often lean in closer and closer to my lens, sometimes peeking over the top of the camera, sometimes practically squirming into my lap as I operate the camera and they try to hug the lens.

The truth is, if you want it to appear that the subject is looking at the audience, then he must look directly into the lens. Cheating the eyeline closer and closer never looks quite the same. But it’s difficult for non-professionals to stare into a lens and answer questions, pretending the lens is the person whose voice they hear, without a glassy-eyed look.

A breakthrough in eyeline management came with the invention of the Interrotron by filmmaker Errol Morris, who has used it in his film Fog of War, TV series First Person, commercials for Apple’s “Switch” campaign, and several short films shown at the Academy Awards.

His website quotes an interview with FLM Magazine: “On television we’re used to seeing people interviewed sixty-minutes-style. There is Mike Wallace or Larry King, and the camera is off to the side. Hence, we, the audience, are also off to the side. We’re the fly-on-the-wall, so to speak, watching two people talking. But we’ve lost something. Direct eye contact.

“We all know when someone makes eye contact with us. It is a moment of drama. Perhaps it’s a serial killer telling us that he’s about to kill us; or a loved one acknowledging a moment of affection. Regardless, it’s a moment with dramatic value. We know when people make eye contact with us, look away and then make eye contact again. It’s an essential part of communication. And yet, it is lost in standard interviews on film. That is, until the Interrotron.”

Morris’ contraption — not an invention, really, but a clever application of existing technology — uses two teleprompter setups for an interview. The subject faces the main camera. One teleprompter covers the lens of the camera with a hood shrouding a half-silvered (semi-reflective) mirror. The camera lens can see the subject clearly through this two-way mirror, but the subject, when looking directly toward the lens, sees the reflection of a video monitor rigged to the front of the prompter.

When used for teleprompting presidents or news anchors, this monitor displays the text of the script, fed by a laptop computer. But in an Interrotron setup, the subject sees a video image of the interviewer on the mirror.

The interviewer, sitting comfortably across the room or in another room with a similar prompter-and-camera setup, can see the subject in the reflection of his own video monitor. Thus they can see each other and converse while each appears to look at the camera.

I’ve used the Interrotron numerous times for projects in Silicon Valley and about a dozen other locations around the US and Europe. The eye contact can be startling and revealing, especially when the subject speaks directly to the interviewer in an intimate way. But the system is not perfect.

First, it’s not cheap. A teleprompter can cost $300-500 per day to rent, and you need two of them, as well as a second camera and lighting for the interviewer (though if the eventual product is a single-camera interview, the second camera can be consumer-grade and the lighting perfunctory).

Also, I can tell you from long experience that every teleprompter sets up differently, so it’s prudent to allow an extra hour of setup time for the Interrotron, especially if you’re dealing with a small crew and a new prompter system in a new city. Another difficulty can arise when the teleprompter monitor, usually used in a high-contrast mode to display text fed from a computer, has trouble showing a full-screen, full-color, or even full-gray-scale image of the interviewer from a video camera.

With traditional prompters carrying older CRT tube-type monitors, it was never fun to have a teleprompter mounted on the camera, especially if the camera needed to move (imagine trying to execute a grand jeté with a breadbox strapped to your chest). Most prompters now come with lightweight LCD screens. Though this often means you’re toting around less additional weight, some prompter companies have merely adapted the old, heavy steel monitor supports to the newer monitors, so you might still have a load attached to the camera. If the shot is fixed, the prompter can be set on a separate stand in front of the camera, but this means both must be raised and lowered together if you change height or position during the shoot.

Recently I’ve started using a device called the EyeDirect (it was formerly named the Eyeliner, which I think is a much cooler name. I couldn’t figure out why they would change it, until I Googled Eyeliner and ended up with sites for Maybelline, Cover Girl, and Chanel).

The EyeDirect uses the principle of the teleprompter to tame the wild eyeline. The camera looks through a semi-reflective mirror, in a camera-mounted configuration much simpler than the Interrotron. It was invented by Steve McWilliams http://www.mceyeliner.com/ and is sold by VFGadgets http://www.vfgadgets.com/grip-camera/eyedirect-16×9.

The EyeDirect employs a double-mirror system in a lightweight plastic housing, which mounts directly onto the camera tripod. It takes only about 10-15 minutes to set up, mostly for changing the baseplate under the camera, and about the same amount of time to break down.

The interviewer stands next to the camera and sticks his face into one of the mirrors. The subject sees the interviewer’s face reflected directly over the lens, which brings the eyeline straight down the barrel of the lens. The audience feels he’s looking at them.

If you plan to use it frequently, the EyeDirect will provide great cost savings: about $1500 to purchase the basic unit, plus another $425 for a rolling Pelican case. They even have a small LCD teleprompter monitor for another $325. Not dirt cheap, but remember you could spend $500-1000 per day to rent two teleprompters and an extra camera. The rig can also be turned, so that the camera operator can ask the questions himself and still maintain eye contact with the interviewee. The EyeDirect unit itself weighs just over 11 lbs.

It’s simple and elegant, though a bit under-engineered for my taste. After setting it up and breaking it down dozens of times in recent trips to the Netherland, Belgium, China, and all around the US, I wish the plastic were a bit heavier and the fittings a bit sturdier. Also, the lens cut-out hole just barely fits the Zeiss DigiPrimes and large Fujinon zooms I often use.

No system is perfect. In some situations, we need to add some light to the interviewer so that the subject can see him better through the mirror.

Some interview subjects experience Disjointed Eyeline Syndrome and have trouble looking at the interviewer’s face in the mirror, when they can clearly see his/her body off to one side (see picture). In these cases, we place a camera flag in front of the interviewer’s body to force the subject to look at the face. Using the EyeDirect means interviewers are back squeezing in near the camera, sometimes craning in uncomfortable positions to get their faces into the mirror. But at least they’re not in my lap anymore!

All the photos and frame grabs in this post are from my recent work in HD (except for the old movies!).

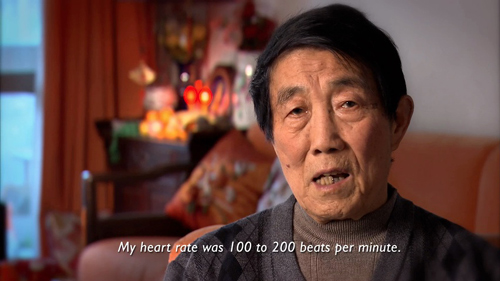

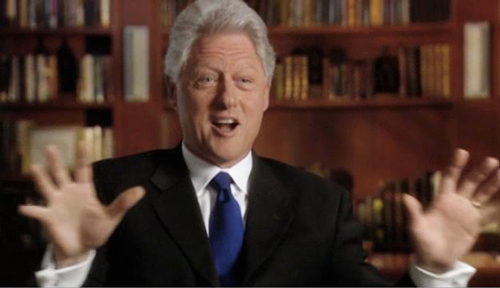

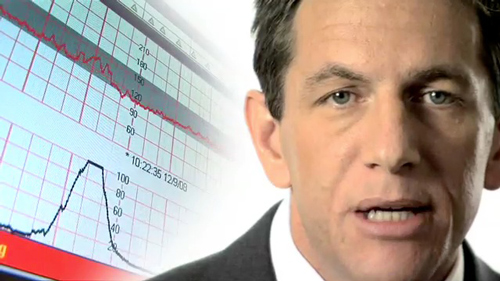

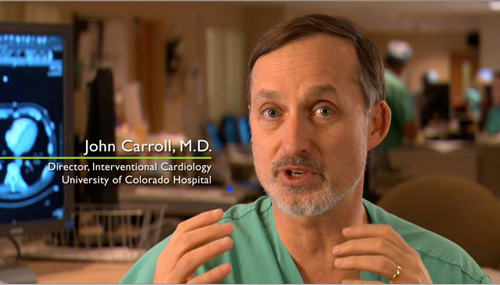

Here’s a gallery of recent closeups I’ve shot with the EyeDirect:

Taming the Wild Eyeline…enjoyed your technical insight.

Interesting post. Thanks Bill.

Have you tried the EyeDirect HDV with your 5D Mark II?

Hey Brett, Nope, haven’t tried that combination yet, but I’m sure it will come up.

I’ve often wondered how teleprompters are set up, and had no idea there was such a thing as an interrotron. Thanks for throwing some light on the subject.

Thanks Bill. I enjoy reading your blog.

They provide plenty of useful info and; great images too.

Thank you so much for this valuable knowledge. Didn’t learn that in film school:)

Pingback: Continental Drift « Roving Camera: Bill Zarchy's Blog

Pingback: Around the World in 11 Days: Part 3 « Roving Camera: Bill Zarchy's Blog