(Originally published in HDPro Guide magazine, 2014)

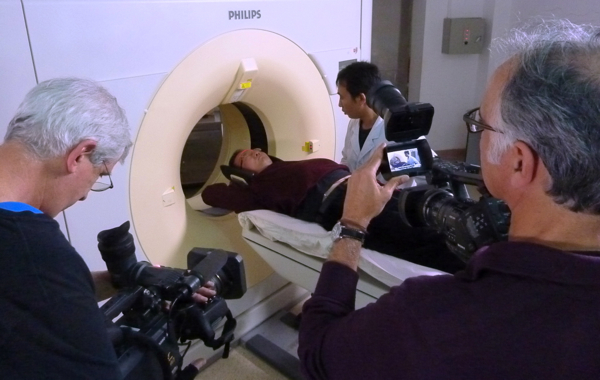

It’s still dark out as we pull up to the hospital on a frosty Chicago morning at six. One of the nurses greets us quietly, and we roll our cameras, monitors, lighting, and audio equipment through the bowels of the hospital to the corridor with the operating rooms. In two hours we’ll be filming heart surgery.

We spend the time gowning up and cleaning our gear, chatting with the staff, and going over, for the umpteenth time, where to position ourselves, when to put on our x-ray protection, how often the lights will go off and on during the procedure, how long we’ll be shooting continuously. Once the nurses and techs have prepped the room and the patient, the doctors arrive and things get going quickly and calmly.

The main doctor, whom we will interview later in the day, makes a small incision in the patient’s upper thigh, inserts a catheter in the leg artery, and pushes it up through the chest into the heart. This patient, who is awake the whole time, receives a wire mesh stent to keep open a collapsing or occluded artery near his heart. The whole thing takes less than an hour, with little or no pain. Miraculous.

Despite a recurring nightmare that I will asphyxiate a patient by standing on his oxygen line during an operation, my crew and I manage once again to comport ourselves well. The procedure is a success. The patient, remarkably, will be up and walking about later the same day, with relief from the chest pain and fatigue which brought him in.

Things certainly have changed.

When I was a young pup starting out, I worked as a camera assistant for a local San Francisco crew shooting brain and open-heart surgery. The blood and the sounds and smells of a power saw cutting through cranial and breast bone repulsed me like a scary horror movie, about as bad as it gets.

Since that grisly beginning, I’ve worked in many different medical settings — on psychiatric training films for pharmaceutical companies, marketing films for medical imaging and equipment companies, TV series on medical ethics, and broadcasts to teach doctors new methods. Shooting medical films can be immensely rewarding—promoting products that have profound effects on people’s lives, more so than when our mission is selling paint, cosmetics, or the latest Silicon Valley widgets.

Much of my work in recent years has centered on minimally invasive procedures, starting with coronary angioplasty, a scientific triumph from the 80s: a doctor inserts a catheter through a small cut in an artery in the thigh, carrying any of several instruments through the arteries in the chest and into the heart, and sometimes into the brain. Small incisions, greatly reduced trauma to the body, often no general anesthesia. The vast majority of cases have successful outcomes.

Besides the stent insertion, I’ve filmed medical teams performing these miracles in the U.S., Europe, Asia, and South America:

- Inserting and inflating a small (and expensive!) medical balloon to open up occluded cardiac arteries

- Scraping plaque out of the arteries around the heart with an abrasive tool the docs all call the “roto rooter”

- Filling a brain aneurysm with platinum

- Using coronary ablation, a carefully pinpointed electrical shock, to zap an atrial fibrulation patient’s irregular heartbeat back into rhythm

- Using cryoablation to freeze abdominal tumors

- Probing various parts of the heart and other organs with the aid of rotatable, three-dimensional, color imaging

Our projects focus on the use of CT Scan, MRI, x-ray, ultrasound, and other advanced medical imaging techniques to diagnose and treat heart ailments or brain, breast, and prostate cancers, among others. In most cases, we interview the doctor and the patient to discuss the dangerous or debilitating conditions forcing these interventions, and to highlight often-dramatic improvements in quality of life afterward.

When shooting medical personnel performing miracles, it’s always important to do your homework, play by their rules, and crank up empathy for the patients.

Useful guidelines for shooting medical procedures

- Scout before the day of the shoot. Nobody like surprises, especially health care givers. Show up for your shoot with plenty of time to inspect your location and to meet and plan with the personnel involved.

- Remember that filming people at work, no matter who they are, means that you’re disrupting their day. Some may welcome the diversion, but never forget that health professionals’ first priority is patient care, not your project. Figure out how to get what you need while staying out of their way.

- Plan to arrive early on the day of the shoot. For surgery or other procedures that involve a lot of prep, come in with the nurses and techs, and set up as they do.

- Clarify where the sterile areas are, and stay away from them. For surgery that involves large, open incisions in the body, the entire operating room could be a sterile field. For minimally invasive procedures with tiny incisions, there is usually a smaller sterile area near the instrument table. During your scout, work out your physical access with the nursing and technical staff.

- Find out how long the procedure will last. If you need to leave before it’s over (as is often the case), work out your escape plan for easy egress, making sure your cables are not trapped and you can get everything out the door without disturbing the team.

- Understand that the doctors are invariably the stars, but the nurses do the real patient care between visitations by the docs. In many cases, the techs are the ones who really know how to drive the high-tech medical toys. There are often four to six medical personnel in the room — docs, nurses, and techs — plus one or two from the film crew.

- Discuss the lighting in the procedure room with the people who work there. Most rooms have fluorescent lights overhead, plus a powerful, adjustable surgical spotlight. The staff might have a particular workflow for the room lighting, or they might be willing to let you replace their overhead lights with lights of your own, such as a Kino-Flo in a corner of the room (better for color and angle of the light). In Europe, I’ve seen a few “Ambient Rooms,” procedure rooms with fancy colored lighting to calm the patient, but these are quite unusual.

- Ask about sound. Many medical procedures are accompanied by music, to soothe and amuse the medical crews standing and working for hours together. If you need to record dialogue, they might be willing to forego their tunes. But ask ahead of time.

- Find out if the patient will be awake during the procedure. If so, interaction between patient and doctor could provide some interesting dialogue for your film. In one procedure in Belgium, the doctor and patient shook hands at the end of the procedure — on camera.

- Respect the privacy, personal space, and possible embarrassment of the patients around you. I often try to maintain a respectful professional distance, avoiding eye contact with patients on a ward or in rooms off a hospital corridor. Above all, don’t gawk.

- Remember that hospitals are full of germs, and many of these are on the floors.

Years ago, my crew and I were shooting in a hospital south of San Francisco. After several days, we started to wrap our video and electric cables to move to another department. One of the nurses, who had been working with us all week, told us suddenly, “After handling those cables, make sure you wash your hands before you eat. You know, this place is full of sick people.” Good advice, as it turned out, because there was a staph infection rampant in the hospital at the time. Unfortunately, she didn’t convey this safety tip until Day Four, and about half the crew (including me!) fell sick with intestinal agony, some for as long as two weeks.

- Expect to wear hospital scrubs, gowns, head and mouth covers, and booties (to protect the patient from your germs), and lead jackets, vests, and collars (to protect you from x-rays). Follow carefully the instructions of the nurses and technicians. Often the lead, which can be very heavy, is only necessary during part of the procedure.

- Make sure the medical personnel on camera are properly decked out. I’ve wasted hours shooting demonstration procedures with staffers who were not wearing the correct head covering. They should know what they’re doing, but it never hurts to ask if everything — equipment, garb, and personnel — will look correct to the discerning eye.

- Be prepared to swab down your equipment with alcohol or other antiseptic. This is for the protection of the patient, and the hospital staff will instruct you on proper protocol. No one expects you to slosh alcohol on your precious lenses or douse your electronics, but it’s a good idea to clean your gear ahead of time, especially the horizontal surfaces that have trapped dust and dirt. Allow time for this important step.

- Plan to use two cameras, if possible, because your ability to change camera angles could be quite limited. Depending on the size of the procedure room, it might be impossible to get decent coverage from only one angle and difficult to move around. Typically the doctors face a bank of video monitors displaying the very latest in medical imaging (often made by our clients). You’ll need two angles to illustrate this basic setup and shoot close-ups of the screens, much less get an establishing shot or an angle on the patient. If the procedure involves magnetic resonance equipment, you won’t be able to bring any equipment with metal inside the main door of the MRI room, though you might be allowed to leave that doorway open and shoot through it.

- Use longer focal length zoom lenses. You often won’t end up too close to the action, and a long zoom will allow you to frame up close shots. Use a tripod to shoot procedures; you might have to roll for an hour at a time. A tripod with wheeled spreader can be quite useful, if you have the room to move around at all. We often use a camera cable back to a video engineer who monitors and shades our shots as we continue to roll through various changes in room lighting. The casters on the Sachtler wheeled spreaders have an adjustable cable guard, so you can push your camera or monitor cable in front of you as you roll to a new position.

Filming medical procedures requires you to be responsible and empathetic. Recording a sensitive operation is a privilege not to be taken lightly. Remember that the most important thing — really, the only important thing — is the wellbeing of the patient. If you establish the rules with your medical hosts ahead of time, respect their needs, and stay out of the way, you might be present at the moment when someone’s health starts on the road to dramatic improvement.

Some basic precautions for shooting in someone else’s work space

In addition to respecting the special conditions of medical procedures, take these basic precautions in all locations:

- Find out where power is available for your equipment. Don’t plug your lights into the same circuits as any medical or computer equipment. Bring plenty of stingers — AC extension cords — so you can bring power in from other rooms if necessary.

- Secure your cables so that people don’t trip on them and carts and gurneys can avoid them.

- Tape down lightweight cables by running gaffer tape perpendicular to the length of the cable.Cover heavier cables with rubber or carpeted floor mats.

- Try to avoid running tape along the length of the cable; this increases the chances of the two sticky sides touching and fusing together when you futilely try to remove them. When it’s time to wrap, pull up on the tape, not the cable.

- Whenever you use gaffer tape or other sticky film-industry tapes, always fold back the end about a half inch to form a tab. This will make the tape much easier to remove later, especially on carpet after being stepped on all day during production.

- Fly cables over doorways and halls whenever possible, especially in locations where beds, gurneys, or carts pass by regularly.

Excellent article; very well written and informative. I like the outfits you are dressed in especially the picture of you in the protective orange vest. However,I couldn’t see the skirt. These medical procedures are amazing and your guidelines for shooting medical procedures was inclusive and thorough as were the basic precautions for shooting in someone else’s work space.

Keep up the great writing.