Singapore Journal

“Who watches all those cameras?”

By Bill Zarchy

“Beer? Beer? Beer? Beer? Beer?” The satay sellers, each wearing a pink plastic bag on top of his head to keep off the driving rain, sized us up and pointed to each person in turn, calling out with great enthusiasm. Caught in a downpour and ready to devour the tasty Thai meat-on-a-stick delicacy, my film crew and I huddled tightly around a table in the Satay Club, only partially covered by a narrow umbrella. Alas, that was nine years ago. The Satay Club—really a group of outdoor stalls in a park across the street from the Westin Plaza, near the Raffles Hotel—is gone now, and the park has been redeveloped into an arts center and a memorial. No beer. No satay. Looking around, I recall a dinner in Singapore years before at a place recommended by some friends back home: the Apollo Banana Leaf Indian Curry Restaurant. When we were seated, a gaggle of waiters slapped down huge banana leaves in front of each of us, to serve as place mat and plate. Then came to each of us in turn, asking, “Rice?” “Chicken?” “Vegetable?” “Curry?” “Fish head?” until they had offered all six or eight dishes on the menu. If we said yes to any choice, they would slap large dollops of that item down on the banana leaves, then move on.

The food was delicious and incredibly spicy. We were each provided with a small, dry washcloth to use as a napkin. I sweated buckets, consumed gallons of water, and visited the toilet several times to throw water on my face and rinse out my washcloth. As we left, I noticed my hands seemed permanently stained red. The Banana Leaf is still there, so far surviving the constant spread of high-rise projects. Over the years, Singapore’s government has systematically destroyed ethnic neighborhoods and replaced them with high-rise apartments. As a result, with the exception of a few areas— notably Chinatown, Little India, and Arab Street—most of the city is modern and characterless. The old and the new have been replaced by the new and the newer. Nevertheless, Singapore is a favorite destination for Americans and other Westerners who like its lush greenness, its cleanliness, and its shopping. In fact, the city is great for gringos who don’t really like to visit other countries: If you don’t make an effort to get out and sample the local cuisine, you can stay in a Western hotel and eat Western food for your entire visit. And it’s perfect if your purpose in traveling is buying clothes, watches, handbags, and shoes, even though the prices are often comparable with those in the States. |

Raffles As

I bravely traipse out of my hotel for a neighborhood walk through

the torpid air, it occurs to me that the restored The

Plaza is connected to a Swissotel and attached to the Raffles City

Shopping Center, a five-level mall inhabited by stores like Mont

Blanc, Lego World, the Museum of Modern Art Store, Mrs. Fields’ Cookies,

Burger King, Orange Julius, a variety of restaurants and food courts

and electronics, clothing, and record stores, banquet halls and ballrooms

for weddings and other events, even a supermarket in the basement.

The air is chilled to a temperature that could keep ice cream at

a thick consistency. In one corridor called “Peacock Alley” between

the Plaza and the Swissotel, I’m sure I can see my breath as

I hurry through, shivering. Maybe that’s a good thing: Singapore is only 120 miles from the Equator, so the temperature outside averages near 80 year-round, and the humidity is always high. It’s tempting to stay in the hotel and shop and eat in the mall, venturing out into the muggy weather as little as possible. The

weather is almost the only thing that hasn’t changed since

my first visit to Singapore in 1975, hired to shooting a travel film

for Pacific Delight, a Hong Kong-based tour operator. We followed

a group of older American tourists (called “geese” in

the travel trade), on their Orient Escapade—a one-month, eight-country

trip around the Pacific Rim. |

Return I returned to Singapore 18 years later, part of a round-the-world shoot at the manufacturing facilities of a Japanese electronics company. By then, this island city-nation on the tip of the Malay Peninsula had acquired a repressive reputation. Huge signs shouting “Death to Drug Traders” greeted us at the airport, and stories of people being arrested for discarding chewing gum on sidewalks were common. During lunch on our first day, Randy, our director, came back from the restroom amused by a sign that proclaimed “$100 Fine for Failure to Flush Toilet.” “But

how do they know whether you’ve flushed or not?” he asked

our local crew. “In all public toilets?”

“But that means there must be hundreds, or even thousands of cameras in this city,” said Randy, incredulous. “Who watches all those cameras?” Our friends shrugged and smiled.

I

returned a few years later to shoot a corporate film. In our last

hour in the country, our local production manager treated us to a

diatribe about conditions in Singapore.

Our project this time is for a huge American corporation that makes computer hard drives. We meet our local crew, who perfectly reflect the cultural smorgasbord of the nation: Krishna, our lighting gaffer, grew up in Singapore after his parents emigrated there from Chennai (Madras), India. |

R-r-rock and r-r-roll

We

remember an earlier incident when Randy was complaining to no one

in particular about how bizarre it was to work with corporate executives,

middle-aged “suits,” who like to drop hip phrases like “Let’s

get it on,” “Awesome!” and “Time to rock

and roll.” With a little prodding, we had convinced Malik,

at the beginning of a take, to call out in his sing-song voice, “Okay,

R-r-randy, let’s r-r-rock and r-r-roll!” It struck Randy

speechless with surprise, if only for a moment, but the event stuck

with him.

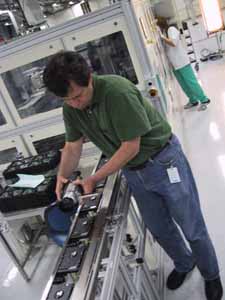

We’re

here to film production that takes place in sterile cleanrooms, where

workers and sanitized machines cut, polish, clean, and assemble parts

for hard drives. For one day’s shooting we will have to dress

in white “bunny suits” that cover all body parts except

the eyes. The specs are quite strict, with an allowable contaminant

level less than one part per thousand. I am always surprised that

they let riff-raff like us into places like these, even after our

equipment is swabbed down with alcohol. We are concerned that the

cleanroom administrators may not admit our rolling camera dolly,

which has spots of rust and corrosion. My biggest problem with bunny suits in Asia is sizing. On a previous trip, the largest suit available was much too small, and at six feet four inches I couldn’t get it on over my clothes. Jane, our producer, took me aside and advised me to go into the men’s room, remove my jeans, and slip the suit on over my underwear. Her suggestion did make it possible to squeeze in, but it was still tight enough to make me fear gangrene. Randy commented that I looked like a sausage packed into a casing that was too small, “like Nureyev on steroids.” I’m sure even a cursory look would have revealed both my gender and my religion, and the effect—bolstered by a treacherous photo taken by one of my companions—has been a source of amusement to them in the decade since. Having learned from that earlier problem, we brought several extra-extra-large bunny suits with us from the company’s facilities in California. But our Singaporean friends tell us these are the wrong type for their cleanrooms, and I’ll be forced to wear something too small once again.

To complete the experience, Adam describes in excruciating detail his unpleasant experience of sneezing in a bunny suit on a previous shoot. Oy. What could be worse than that? The night before cleanroom day, I encounter something more dreadful to anticipate in a bunny suit than a sneeze: diarrhea. In ultra-clean Singapore, where everyone drinks the water and food is usually safe, I contract the gastrointestinal problem known to international travelers variously as la turista, Bali belly, Montezuma’s revenge, or the trots. Fortunately, Imodium is a wonder drug, and by morning, I am sufficiently plugged up to avoid disaster in the cleanroom and more years of teasing from Randy and the boys. Unfortunately, I make the mistake of mentioning my affliction to our crew. Malik is sympathetic, saying, “Oh, I hate those wide-angle squirts, man, they’re awful, like chunky peanut butter!” For the rest of the shoot, I address him as Chunky. Surprisingly,

the suits are less uncomfortable than my worst memories. My biggest problem is recognizing my colleagues. The factory’s engineers wear blue bunny suits, and the systems technicians wear green. But most of the workers are in white, like us. Few Singaporeans reach my height, so I am easy to distinguish. But to me everyone else is, well, shorter. I learn to identify people by their eyes, brows, and glasses.

|

Wrap

Some

of the Malay women wear Muslim headdresses, and the Indian women

have distinctive makeup and jewelry. But most of the workers are

Chinese, the dominant group in Singapore both economically and politically,

and their dress and attitudes are as Westernized as if they were

in California. It’s impossible to avoid the thought that the

machines we are featuring in our film will eventually replace many

of these folks. Malik amuses us with a naughty joke about a man from China who visits New York. When he tries to order food in a restaurant, the waiter brings him a frankfurter. Confused, he asks, “What is this?” “Why, that’s a hot dog,” replies the waiter. “Ah,” he says. “We eat dog, too. But we usually throw that part away.” On

our last day of shooting, we wait hours for the factory engineers

to get their new automated machinery working. Bad robot. The day

drags on, but we persevere, bolstered by a late afternoon caffeine

shot from a local coffee joint. Finally, after less than a week in That night, our clients treat us to Italian food at Prego, a restaurant in the hotel. I order linguine with marinara sauce and Caesar salad. For dessert, I head down to the supermarket in the Raffles City basement for Haagen Dasz ice cream. I realize as I pack my clothes and my gear that I have hardly been outdoors in seven days in Singapore. Except for my initial walk through the Plaza’s neighborhood, I have not left the air-conditioned cocoon of the hotel, the mall, and the passenger van, which delivers us daily to the sterile factory. Jon and Larry went for a long walk down to Boat Quay one evening, but that was the night I was sick, so I missed the outing. Each evening, we returned tired from work, with little incentive to go out on the town.

I

grit my teeth as we prepare to reverse the same roundabout route

back to California. Our group assembles on the curb in front of the

Plaza to load 19 equipment boxes and suitcases into our cargo van,

and I ask Jon with mock alarm, “Jonny, where’s the 17” monitor?

We must have left it at the plant!” But Jon was up late packing the video gear, and his stunned expression bespeaks a befuddled exhaustion. No worry, I think, chicken curry. We shuttle back to Changi to check in three hours early. Contrite over my bad joke, I drag Jon to Starbuck’s to treat him to the corporate coffee of his choice. The clerk greets us, “Hey, guys, what’ll you have?” Iced grande latte and biscotti in hand, it feels like I never left home. |

See another version of this story, as published by Film/Tape World: "No Worry, Chicken Curry"

“Satay? Satay? Satay? Satay? Sayay?”

“Satay? Satay? Satay? Satay? Sayay?”  There

were no utensils. We ate with our hands, Indian style. I tried to

remember the directions from James Clavell’s novel King Rat,

which I had read years before: “Right hand, food hand. Left

hand, dung hand.” Or was it the other way?

There

were no utensils. We ate with our hands, Indian style. I tried to

remember the directions from James Clavell’s novel King Rat,

which I had read years before: “Right hand, food hand. Left

hand, dung hand.” Or was it the other way? Raffles

Hotel, with its arched walkways and white columns, the Long Bar once

frequented by Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, and Somerset Maugham,

is almost all that remains as a memory of the seedy elegance of this

former British colony. The Sarkie brothers, celebrated hoteliers

in Southeast Asia, founded Raffles in the late 19th century. It was

a legendary watering spot in the old trading port, a setting for

intrigue and romance in many stories and novels, and the home of

the Singapore Sling, a sweet pink “women’s drink” made

with gin, cherry brandy, fruit juices, Cointreau, Benedictine, and

bitters. Raffles is now an international hotel chain. Having subsumed

the former Westin property, it bears the awkward name Raffles the

Plaza.

Raffles

Hotel, with its arched walkways and white columns, the Long Bar once

frequented by Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, and Somerset Maugham,

is almost all that remains as a memory of the seedy elegance of this

former British colony. The Sarkie brothers, celebrated hoteliers

in Southeast Asia, founded Raffles in the late 19th century. It was

a legendary watering spot in the old trading port, a setting for

intrigue and romance in many stories and novels, and the home of

the Singapore Sling, a sweet pink “women’s drink” made

with gin, cherry brandy, fruit juices, Cointreau, Benedictine, and

bitters. Raffles is now an international hotel chain. Having subsumed

the former Westin property, it bears the awkward name Raffles the

Plaza.

One

of the tour’s selling points was Singapore’s multicultural

society, the residents a mix of Chinese, Malay, Indian, and British.

Another selling point was the contrast of the old and the new, the

phenomenon of a modern city, at that time an independent nation for

only a short time, rising amidst an Asian culture with a British

colonial overlay. In both cases, these disparate elements seemed

to coexist in apparent harmony. We shot scenes on the street of people

of various ethnicities, and we juxtaposed images of modern skyscrapers

with traditional and colonial buildings during a boat ride on the

Singapore River.

One

of the tour’s selling points was Singapore’s multicultural

society, the residents a mix of Chinese, Malay, Indian, and British.

Another selling point was the contrast of the old and the new, the

phenomenon of a modern city, at that time an independent nation for

only a short time, rising amidst an Asian culture with a British

colonial overlay. In both cases, these disparate elements seemed

to coexist in apparent harmony. We shot scenes on the street of people

of various ethnicities, and we juxtaposed images of modern skyscrapers

with traditional and colonial buildings during a boat ride on the

Singapore River.

Housing

was very expensive, cars were subject to a 250 percent import duty,

and gasoline cost more than double what it sold for a few miles away

in neighboring Malaysia. Singaporeans were stopped on the causeway

to the mainland and their gas tanks were checked. If they had less

than two-thirds of a tank, they were turned back, to prevent them

from filling up in Malaysia. Political dissent was illegal and virtually

nonexistent. He told us about the day he participated in a small

protest rally, returning home to find the police waiting to bring

him in for questioning. This was around the same time that the son

of an American diplomat was subjected to a caning for vandalizing

a car.

Housing

was very expensive, cars were subject to a 250 percent import duty,

and gasoline cost more than double what it sold for a few miles away

in neighboring Malaysia. Singaporeans were stopped on the causeway

to the mainland and their gas tanks were checked. If they had less

than two-thirds of a tank, they were turned back, to prevent them

from filling up in Malaysia. Political dissent was illegal and virtually

nonexistent. He told us about the day he participated in a small

protest rally, returning home to find the police waiting to bring

him in for questioning. This was around the same time that the son

of an American diplomat was subjected to a caning for vandalizing

a car. We

follow signs up stairs, down a hallway, and back to a holding area

for the same gate we left. Soon we are back on the same plane (with

a different crew) for another six-hour flight to Bangkok. Here we

land at 11 p.m. local time, pass through Thai customs with only our

hand luggage (the rest of our gear was sent through to Singapore),

and check into the airport hotel for a shower and four hours sleep.

We return to the airport next morning for another three-hour flight

to Changi Airport in Singapore, nearly 34 hours and over 9500 air

miles after leaving San Francisco. A real butt-burner. Randy and

Wayne, our executive producer, arrive the next day by the same route.

We

follow signs up stairs, down a hallway, and back to a holding area

for the same gate we left. Soon we are back on the same plane (with

a different crew) for another six-hour flight to Bangkok. Here we

land at 11 p.m. local time, pass through Thai customs with only our

hand luggage (the rest of our gear was sent through to Singapore),

and check into the airport hotel for a shower and four hours sleep.

We return to the airport next morning for another three-hour flight

to Changi Airport in Singapore, nearly 34 hours and over 9500 air

miles after leaving San Francisco. A real butt-burner. Randy and

Wayne, our executive producer, arrive the next day by the same route.

If

they don’t, all our shots will be static. “No worry,

chicken curry,” says Malik, and our crew wraps the dolly in

Saran Wrap so it will pass inspection.

If

they don’t, all our shots will be static. “No worry,

chicken curry,” says Malik, and our crew wraps the dolly in

Saran Wrap so it will pass inspection.  On

our scout during the first day of work here, I am reminded why I’ve

never liked bunny suits. Our heads are covered with hairnets and

nylon hoods, our mouths with surgical masks, our feet with nylon

booties, and our bodies with nylon jump suits. Rubber gloves complete

the ensemble, just in case some ventilation might slip through and

the discomfort isn’t total. Even the heavily refrigerated air

doesn’t help. I feel like an overcooked kielbasa.

On

our scout during the first day of work here, I am reminded why I’ve

never liked bunny suits. Our heads are covered with hairnets and

nylon hoods, our mouths with surgical masks, our feet with nylon

booties, and our bodies with nylon jump suits. Rubber gloves complete

the ensemble, just in case some ventilation might slip through and

the discomfort isn’t total. Even the heavily refrigerated air

doesn’t help. I feel like an overcooked kielbasa.  The

booties are at least two sizes too small, but I manage to squeeze

my orthotic insoles into them, and that attenuates my discomfort

level. We trudge slowly through the factory over the next eight hours,

like astronauts on the moon, surrounded by hundreds of similarly

attired workers, gradually filming the newest automated robotic equipment.

We are familiar with this high-tech environment, similar to many

places we have worked in California’s Silicon Valley, Minnesota,

Texas, and elsewhere.

The

booties are at least two sizes too small, but I manage to squeeze

my orthotic insoles into them, and that attenuates my discomfort

level. We trudge slowly through the factory over the next eight hours,

like astronauts on the moon, surrounded by hundreds of similarly

attired workers, gradually filming the newest automated robotic equipment.

We are familiar with this high-tech environment, similar to many

places we have worked in California’s Silicon Valley, Minnesota,

Texas, and elsewhere. The

plant is very noisy. We start to tire as the hours drag on, feeling

the delayed effects of jet lag. Larry has his hands full, working

out the logistics of our shifting schedule, logging shots, and making

sure we slate all our scenes accurately. At mid-afternoon, Jon is

forced to leave the cleanroom to change his mask, which has become

soaked through with the drippings of a bad cold. Randy marches us

through from section to section, lining up shots of the disk-making

process.

The

plant is very noisy. We start to tire as the hours drag on, feeling

the delayed effects of jet lag. Larry has his hands full, working

out the logistics of our shifting schedule, logging shots, and making

sure we slate all our scenes accurately. At mid-afternoon, Jon is

forced to leave the cleanroom to change his mask, which has become

soaked through with the drippings of a bad cold. Randy marches us

through from section to section, lining up shots of the disk-making

process.

One

night I am watching a match in my room with the door to my balcony

open. When Korea scores a goal, I hear cheering from the TV and from

outside. About a mile away I see the lights of a stadium, and I realize

that thousands of fans are watching a game broadcast there, excited

that Korea has progressed further than any Asian team in World Cup

history. I search in vain on local television for baseball news from

home, but eventually I get my fix on the Web with the Ethernet connection

in my hotel room.

One

night I am watching a match in my room with the door to my balcony

open. When Korea scores a goal, I hear cheering from the TV and from

outside. About a mile away I see the lights of a stadium, and I realize

that thousands of fans are watching a game broadcast there, excited

that Korea has progressed further than any Asian team in World Cup

history. I search in vain on local television for baseball news from

home, but eventually I get my fix on the Web with the Ethernet connection

in my hotel room. In

two more days of filming, we document automation being installed

in this “factory of the future.” On most international

shoots, we do “flavor shots,” exterior filming to provide

a visual and cultural context, but not this time. The robots are

the story, and the city is bland and flavorless. We try to illustrate

Singapore’s multicultural society by featuring workers of various

ethnicities.

In

two more days of filming, we document automation being installed

in this “factory of the future.” On most international

shoots, we do “flavor shots,” exterior filming to provide

a visual and cultural context, but not this time. The robots are

the story, and the city is bland and flavorless. We try to illustrate

Singapore’s multicultural society by featuring workers of various

ethnicities.  Randy

and Wayne joke grimly that, from our clients’ point of view,

the title of the film is “People bad, robot good.”

Randy

and Wayne joke grimly that, from our clients’ point of view,

the title of the film is “People bad, robot good.” Singapore,

we say goodbye to Krishna, Adam, Malik, Sam, and Tan, and prepare

for the trip back home.

Singapore,

we say goodbye to Krishna, Adam, Malik, Sam, and Tan, and prepare

for the trip back home.  Looking

around Prego, I wonder: Am I really in Asia? Singapore has become

so Westernized and bland—“deflavorized,” to use

Randy’s word—that we could be anywhere. Krishna had assured

us that vestiges of colonial life like the Padang Cricket Ground

and ethnic enclaves like Little India and Arab Street are still intact,

and that Chinatown was saved by public outcry when the government

proposed tearing it down. I regret not getting out to see these sights

again, but my purpose here has been documenting the factory of the

future, not sightseeing.

Looking

around Prego, I wonder: Am I really in Asia? Singapore has become

so Westernized and bland—“deflavorized,” to use

Randy’s word—that we could be anywhere. Krishna had assured

us that vestiges of colonial life like the Padang Cricket Ground

and ethnic enclaves like Little India and Arab Street are still intact,

and that Chinatown was saved by public outcry when the government

proposed tearing it down. I regret not getting out to see these sights

again, but my purpose here has been documenting the factory of the

future, not sightseeing.  I

think this will be a harmless joke, because the monitor’s huge

shipping case sits on the sidewalk, about a foot from his right leg.

I

think this will be a harmless joke, because the monitor’s huge

shipping case sits on the sidewalk, about a foot from his right leg.