Former White House Director of Communications David Gergen is recalling the unforgettable day that President Reagan and his staff woke up at Versailles Palace, had lunch with the Pope and ate dinner with Queen Elizabeth. My problem, however, is lighting his dark suit without pouring too much light on the top of his head.

Henry Kissinger is describing the peace agreement in Vietnam as a high point in his White House service. But how do I get light in both of his eyes without creating distracting glare in his glasses? And what do I do about the moiré pattern on his tie?

Bill Clinton reveals that he is more idealistic about the presidency now than when he took office, Jimmy Carter tells us he did the right thing by not bombing Iran, and Gerald Ford defends his pardon of Nixon as necessary to heal the country after Watergate. But will their respective shots integrate well with our show, despite differences in setting and lighting? And how do I pre-set these interviews, knowing that I will have a bare 30 seconds to adjust each person’s lighting after he sits in?

These challenges were just a fraction of what I encountered as director of photography for the Emmy-winning The West Wing Documentary Special, which NBC aired on April 24, 2002. During 11 shooting days, in five cities around the country, we created a classic look to suit the subject matter and reflect the grandeur of our locations. Our talking-head interviews of Gergen, Kissinger, Ford, Carter, Clinton, and a dozen presidential aides, shot on digital Betacam, would be intercut with the fictional White House world of The West Wing, and we were constantly challenged to match the shadowy, peripatetic look of the show, which is filmed in 35mm by Emmy winner Thomas Del Ruth, ASC.

Our director was Oscar-winning documentarian Bill Couturié, with whom I have collaborated often over the past year. The West Wing shoots most exterior scenes and some interiors in Washington, and we follow suit in our documentary, carefully choosing, lighting and dressing locations to resemble the grandeur of the White House and other D.C. government temples.

Many former White House staffers are on the schedule as we start our shoot. Former president Bill Clinton has agreed in principle to appear on the show, but only if another president agrees. The Bushes will not be on the show, Reagan no longer appears in public, and Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter are deciding.

In all, I make two trips to Washington, three to New York, one to Atlanta, and one to Rancho Mirage near Palm Springs, with San Francisco-based producer Anne Sandkuhler and video field engineer Jim Rolin. Bill Couturié, who lives in southern California, joins us at each of these venues, conducts all of the interviews, and completes postproduction in Hollywood. Production coordinator Alexis Ercoli also accompanies us on several of these trips.

Our Washington location is at the headquarters of the Daughters of the American Revolution, a block or two from the White House. We set up in the grand President General’s Room, where many presidents, first ladies and world leaders have awaited the start of events in adjacent Constitution Hall, the DAR’s gem of a concert venue.

On our first day, we interview Marlin Fitzwater and Dee Dee Myers, press secretaries to Reagan-Bush and Clinton, respectively, and Clinton adviser Paul Begala. We also scout other rooms in the DAR complex and decide to change locations daily.

We had planned to record this show in HDTV, using that medium’s cinematic qualities and native widescreen format to help blend our look with that of The West Wing‘s fictional material. But budget considerations dictate our shooting in the 16×9 aspect ratio with a Sony 790WS camcorder on digital Betacam. Later, we switch to an Ikegami HL388 camera with a separate tape deck, all from Videofax in San Francisco. Both cameras use 15x8mm Canon zooms.

Fitzwater, Myers, and Begala reflect on their White House days, the trappings of Presidential power, the lack of time for a personal life, the respect and affection for their respective bosses, and the thrill of working for causes they believed in. Begala is particularly exciting and articulate in this trio of Washington pros. He remarks at one point that being in the political consulting business with his better-known partner, James Carville, is “kind of like being Dolly Parton’s feet.”

We wrap out of the President General’s Room and wheel all of our video, sound, lighting, grip, and prop gear through the serpentine cellar of the DAR complex, which actually consists of three interconnected buildings. We emerge in the classic old Museum wing, with wide marble staircases, arched hallways, statuary and enormous paintings. Large items need to be carried upstairs, though a tiny, temperamental elevator is available for small loads. It holds an old brass plaque dedicated to Josiah Bartlett, a signer of the Declaration of the Independence and real-life ancestor of The West Wing’s fictional president, played by Martin Sheen.

Truly, our production value mantra is location, location, location. The walls at the DAR document two centuries of the nation and the Daughters’ history, and marbled corridors connect dozens of ornate rooms, most named after states, some large, some small and roped-off like museum dioramas. We shoot two interviews in the Connecticut Board Room, now famous as the room where former presidential candidate Bob Dole once filmed a Viagra commercial.

Our subjects are lit with a 1200-watt HMI PAR light in a medium Chimera softbox. The Chimera comes with a variety of front diffusions, baffles, and inner diffusions, and the PAR light has several changeable lenses. The Chimera diffusions warm up the 1200’s daylight color, and we typically add an additional 1/4 CTO gel. This key light provides a flattering, controllable, variable, soft, direct glow on the subject’s face, yet it can be moved in a moment.

Bill C. and I have an agreement that, immediately after arrival, I get to see each person for 30 seconds in the interview chair, with the correct eye line and with no one standing in the light. Then they lead him or her off for makeup and prep. But that quick inspection helps the gaffer and me decide whether to raise or lower the key light, bump it more to the side for more ratio, or more frontal for more light in the second eye.

The irony is that we spend hours staging the shot, lighting and propping the background, but we have only those 30 seconds to scrutinize each person’s particular facial topography, wardrobe, glasses, or complexion. Everyone has a distinct facial bone structure, so the light strikes each face differently. During setup, we pick someone on the crew to sit in and model for the shot, someone with roughly the same hair color and build as the subject. But there’s no way to know how the same lighting will look on two different heads.

Bill C. likes to conduct the interviews from near the camera, to bring the subject’s eyeline close to the lens, and usually we have the key on the same side as the interviewer, to face the subject into the light. This rule changes when the subject wears glasses (more on this later).

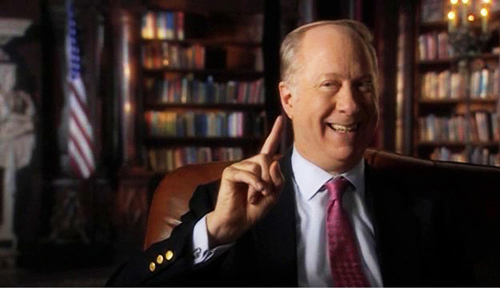

I use no fill, just a 4×4-foot white foamcore card to bounce a bit of ambient light, and we always set a “kicker” — a low-angled, subtle backlight cheek-scrape opposite the key side, using a daylight Kino-Flo fixture and lots of diffusion. With dark-haired subjects, I might add a top backlight, but generally I’m not a big fan of hair lights, especially with balding, middle-aged politicos. Usually we bounce a little light on the tops of heads with another 4×4 card. We use this method for David Gergen’s interview.

In the background we deploy a combination of small HMIs, Kino-Flos, and Source 4 Lekos. The HMIs, usually 200- or 400-watt Jokers, give us splashes of cool light. The Kinos provide warm or cool ambience, using tungsten or daylight tubes. I use patterns with the Lekos, but always for abstract texture, never as a representation of an arched window, blinds or a floral pattern. The Lekos streak in from the sides, their patterns distorted and softened, dappling and texturing bookcases, walls, and furniture. We let the Lekos keep their natural warm tungsten look to mix with the cool background lights. Since our portrait lighting scheme is the same for each subject, we spend much of our setup time designing and lighting the backgrounds.

Our camera is usually about three feet off the floor on a focal length between 30 and 45 mm. Early in The West Wing shoot, we did occasional slight zoom moves during responses. After the first day or two, Bill C. and I decided instead to let the interview play out within a single frame. The subjects are eight to 10 feet away, sitting on a small plywood platform built on quarter or half apple boxes. This setup provides a slight up-angle on the lens for a pleasing perspective against the background, even though we have a propmaster to hang paintings and adjust furniture.

I have shot many talking heads and always hate to center faces, so I compose each shot with the head bisecting the left or right half of the 16×9 (1.77:1) frame. Anne keeps track of the eyeline in her production notes, and we shoot about as many interviews with eyes left as eyes right.

Over the years, I’ve used a great variety of tools and gimmicks during interviews. Some directors like to film interviews from a moving camera, some use abstract backgrounds (such as a grey mottled canvas backdrop painted with light), some use greenscreen backgrounds (for later insertion of relevant B-roll material, or eye-candy graphics), some like to have the camera dutched and dollying, or to frame close-ups with people’s noses bumping the edge of frame.

For The West Wing documentary, we’ve decided on a consistent, classic approach to composition, a comfortable head-and-shoulders shot for each person. I encourage subjects to “be Italian,” to talk with their hands, and Bill C. prefers them in chairs with arms, so their hands appear in frame. We often exploit and enhance the depth in our locations, with a window or lamp deep in the frame.

We use a 12×12-foot black double net behind our interviewees to soften and distance the backgrounds, a technique I have often used with Bill C. Gaffer Bob Waybright from the Washington Source also has 8×8 foot nets that will do the same job in a small space, but we prefer the 12×12, which we can push further back and out of focus. It’s vital to keep stray light off the net, which can raise the background black level.

This 12×12, along with a coarse black bridal-veil net on the rear element of the lens, helps to create a soft, cinematic image for our talking head, especially in a recording format as potentially sharp as digital Betacam. Jim Rolin and I keep the “details” circuit on the camera set fairly low to minimize electronic sharpness. We white-balance from the key light, then warm up the picture electronically from that base setting. We carefully control the camera’s black level to avoid letting the background net or the bridal veil on the lens milk out the picture. The nets should provide softness and texture without compromising rich blacks.

In the Viagra Room at the DAR we interview Betty Currie, Clinton’s personal secretary for eight years, and current owner of Socks, the presidential cat. She warms our hearts by recounting the thrill of having her mother and sister meet the president, shortly before her mother’s death. We turn the camera around and face the opposite corner of the Viagra Room, setting up for Lanny Davis, a White House staffer who describes himself, off camera, as the “flak sponge” during a particularly contentious, scandal-ridden time in Clinton’s second term. Lanny wears new glasses with a great anti-glare coating, and we bravely face him into the key light. Someday I want a spray can of that coating.

We shift to the DAR Library, a magnificent open reading room, the original Constitution Hall, before the current auditorium was opened in 1929. Here we talk to Gene Sperling, a vital cog in Clinton’s brain trust, widely credited as the hardest-working of that famous group of workaholics. He is seated on a balcony over the reading room; behind him, 50′ away, loom a golden eagle and a magnificent arched ceiling. The shot has fantastic depth, so we don’t need our 12×12 net in the background.

On our last day in D.C. we set up in the DAR’s O’Byrne Gallery, a magnificent long room with huge French doors along one wall. I call it Versailles. When the DAR library was still a theatre, the O’Byrne was its grand foyer. The West Wing often uses the colonnaded portico just outside as a location resembling the White House. To take full advantage of this magnificent space, we set up the camera with our backs to the wall.

Our subject here is Ken Duberstein, former chief of staff under Reagan. He is rhetorical, dramatic, and riveting. His voice rises in power and intensity, then drops to an emotional whisper as we watch his performance, open-mouthed. We quickly fill two half-hour tapes. Duberstein seems inexhaustible, but he does have a plane to catch. A car whisks him off when we’re done.

Days later in Manhattan, our interview with Gergen is at the House of the Redeemer, a former Vanderbilt mansion on East 95th, in a huge, library-like setting. New York gaffer Don Muchow, key grip John McElwain and I enjoy painting this rich environment with light, streaking and dappling dark wood, books, mezzanine, and a few bright sconce lights in a shadowy background. The 6’4″ David Gergen has a spellbinding presence; he’s eloquent, professorial, articulate and polished. He tells tales of life under four presidents, stories that go on for five minutes — an entire century in the too-quick world of television.

The next day, we interview Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan and a young Clinton aide named Michelle Crisci at the Soldiers and Sailors Club on Lexington. This hotel for members of the armed forces, retirees, and veterans was founded in 1919 and has a living room with the right kind of elegance. Noonan tells us of her defiance of the request that she write speeches for Nancy Reagan, which stems from her worry that she would be seen as “the woman speechwriter.” Now, however, she admits that “I couldn’t have done anything dumber.”

Clinton chief of staff Leon Panetta and several young former Clinton aides are on our agenda the following week, in the Chairman’s Suite at the Westin St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, a lovely wood-paneled, book-lined location with a second floor of bedrooms, and an internal staircase and balcony. Panetta is warm and avuncular, with a gleam in his eye. When he hears me address gaffer Jon Fontana by name, he smiles at Jon and calls him “paisan.” He tells us that when he heard that the chief of staff on The West Wing was named Leo, he just hoped he was a nice guy.

Here I break my rule on facing the subject into the key light. The closer the interviewer is to the lens, the harder it is to eliminate reflections in glasses. I always try to keep the key at least 45 degrees off axis to maximize ratio on the subject’s face, but I usually cross-key people wearing glasses, facing them out of the key light. This way, I can often push the key far enough to the side to get good ratio and good light in their eyes, the “windows to the soul,” without fighting reflection. Glasses have always been a problem, especially with the huge convex styles of the 1980s and early ’90s. Lately, more people wear small, flat lenses, some with effective anti-glare coatings like Lanny Davis’. But the closer the questioner is to the lens, the harder it is to eliminate glare in the lenses unless we cross-key.

By the end of the day with Panetta, Anne tells us that we finally have an appointment with Jimmy Carter on March 21st, a whole month away, and about four weeks before the airdate. After Panetta, we are done shooting for a couple of weeks.

Early in March we are back at the DAR, in the Pennsylvania Foyer, a marbled hall lined with flags, paintings, and busts of prominent American statesmen. We set up for Karl Rove, a political strategist in the current Bush Administration. Our 12×12 in the background brings down the level of a distant glowing window and softens the background pleasingly. We paint a combination of warm and cool light, in soft washes and patterns, on the marble sills and walls and statues and flags in the background. Rove is our only subject from the current White House.

In New York two days later, we meet former National Security Adviser and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Rodgers & Hammerstein Suite at the Omni Berkshire Place Hotel. A wrap-around terrace outside the suite enables Don Muchow to light an arched window in the background of Kissinger’s shot and block the sun from blasting in.

We were told we would have Dr. Kissinger for 45 minutes, less if he decides to leave sooner. Kissinger, nearly 80, arrives in a jovial mood, accompanied by his aide and, for some reason, his brother. He looks older than I remember, but his deep, richly accented drone rings a familiar bell. I use my 30 seconds with him in the chair to inspect our lighting, and I am horrified to see that the fine design on Kissinger’s tie causes a distracting moiré that dances and pulsates as he talks. This interference pattern is a common problem with tweedy or herringbone patterns on men’s clothing, and we are grateful when the former Secretary of State readily agrees to switch ties with his brother.

As we did with Panetta, we face Kissinger out of the key light, though his glasses are not as thick and large as in his heyday. We find a good angle for the key light, with a bit more ratio than some of our subjects, and I am happy with the results.

Dr. K peeks at his watch several times during our 22 minutes of videotape, but always during questions. He enjoys reminiscing about his days at the nexus of power in the Nixon and Ford administrations. Bill C. asks good questions, some prompted by the writers from The West Wing , about process and style, rather than issues and politics. This show is a memory piece, not a political forum, and that’s why many of our subjects have agreed to participate.

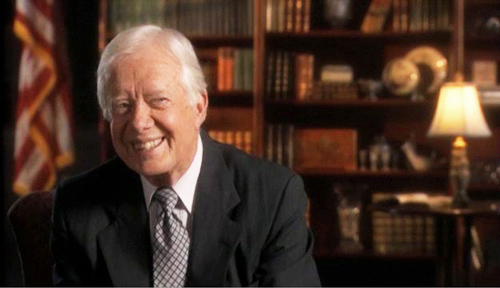

In Atlanta two weeks later, we are offered a small study for our interview with former president Carter. Instead, we arrange to set up at the Carter Center in the Cecil B. Day Chapel, a large auditorium, where we bring in bookcases and lamps and furniture and create a presidential office set. Once again, our background net softens and distances the background. Gaffer Denny Mooradian sets an extra fill light to smooth out any facial imperfections, but we don’t need it for the interview.

We have President Carter for 30 minutes; he arrives exactly on time and we are ready. We study him in the chair intently for 30 seconds, make him up, and turn him over to Bill C. Carter is 77 and grayer than during his term in office, but he glows with a sharp mind, a gentle wit, and a twinkle in his eye. He discusses the difficulty of unpopular decisions that could put Americans in harm’s way or devastate civilian populations abroad. Sometimes, he notes, these policy choices can cost an election, as his own actions in the Iran hostage crisis did. His articulateness, his warmth, and his candor are impressive. Bill C. enjoys concluding the interview with “Thank you, Mr. President,” we take a group photo with Carter, and he is gone, 30 minutes and 40 seconds after arrival.

We are all delighted. Our shoot has come to the end of a long road, and it seems unlikely the network will pursue more interviews: now we have a president, and the airdate is only weeks away. “We’ve got to stop meeting like this,” says Bill C. to Jim and me. He needs uninterrupted time in the editing room with editor Terry Schwartz. We say goodbye to Bill and our Atlanta crew and wish each other well.

We already have 17 interviews and more than 400 pages of transcripts, and the historical weight of our story is compelling. Our subjects consider public service a noble and uplifting profession, despite the political maneuvering and personal sacrifice. They all miss their time in the White House, except Rove, who is currently ensconced there. Any would go back in an instant.

Except for postproduction, this job is over.

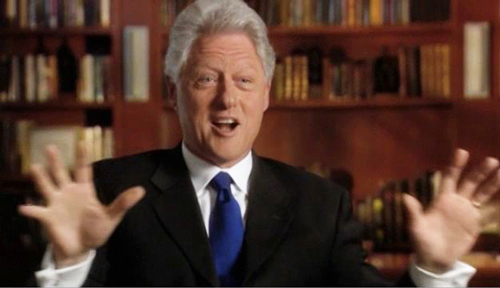

Or so we think. Ten days later, Anne calls. Clinton is back from Australia, she says, and he is interested in appearing on our show, now that we have interviewed Carter. Soon we are back in New York, setting up in Clinton’s office, a long room with 40′ of south-facing windows. The view is a unique perspective from the 14th floor of this federal office building in Harlem. As I look across Central Park from the north, the Empire State Building is now the tallest building in the skyline, and I wonder if Clinton was here on September 11.

We once again shoot with the wall at our backs, the length of the office behind Clinton, his desk and bookcases deep in the background. We don’t plan to see the windows here, so we cover the glass with black Visqueen plastic.

Gaffer John Merriman sets our usual portrait lighting, and we paint the background with cool washes from the HMIs and Flos and warm streaks from the Lekos. Because the office has great depth but is only slightly wider than our 12×12, we forego the background net, which would gobble up the room and restrict access. Clinton’s staff tells us this is his first television interview there, other than a brief statement at his desk after September 11 with a news crew. This is also the only interview where we show anyone in his own office.

The former president is gracious and jovial and clearly enjoys meeting people and exchanging ideas. He looks trim and fit in a well-cut suit, and I am struck by how young and vital he appears. His hair is whiter than I had anticipated, so we turn off the minimal hair light we had planned. His daughter Chelsea, who was on our plane from San Francisco the night before, shows up at the office later in the day.

Clinton loved the presidency and tells us he ended his tenure in the White House more idealistic than when he started. He loves to talk, and sticks around for pictures and chat after his interview. When asked about his future plans, Clinton mentions that former strategist James Carville recently told him that they are both eligible to run for President of France. Because Carville and Clinton were born in Louisiana and Arkansas, respectively, both parts of the formerly French Louisiana Purchase, they could move to France, establish residency, and run for office. “I don’t think I will,” says Clinton, with a broad smile. “I’m sure I would soon start to take flak for my French accent.”

As we wrap out of Clinton’s office, certain that this shoot is now over, Bill Couturié gets a call. “Hey, we got Ford,” he calls out to me as we head to the elevator. “What, commercials?” asks one of our local crew. “No, Gerald.” Of course, it makes sense. Now that we have two Democratic Presidents, the show needs a Republican.

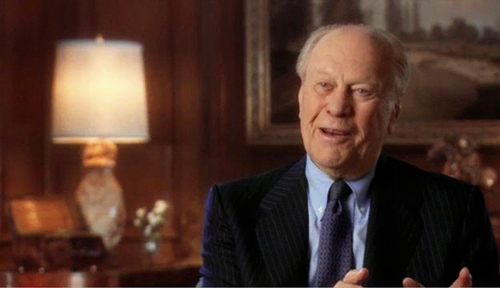

Later that week, and less than two weeks before our airdate, we interview former president Ford in the Board Room at the Lodge at Rancho Mirage, near Palm Springs in Southern California. The room is paneled, cozy and smaller than we would like, but the double net helps the background to recede. Gaffer Larry Roth and his crew dash around making it all beautiful.

“The guys at The West Wing are all jealous,” reports Bill C. “No one gets to talk with three presidents in a month.” We had heard earlier that Ford was ill, but the former president, now 88, has a spring in his step and looks much as he did when he succeeded Richard Nixon in 1974. “You guys just don’t age,” says Bill C. when he meets Ford.

The Michigan Republican has an easy laugh as he answers the questions clearly and articulately. He is particularly earnest and candid in defending his pardon of Nixon, maintaining that he needed to get the problem “off his desk.” Ford is proudest of the fact that he came from a broken home and rose to be president of the United States, a “tribute to our system.”

At last our shoot is really over. The show airs 12 days later and is a great success. The blending of the interviews with the fictional scenes is skillful and poignant. And getting three ex-presidents to participate in anything together is a unique achievement and a matter of some historical significance.

© 2003 Originally Published by American Cinematographer Online

http://www.theasc.com/magazine/mar03/westwing/index.html

I couldn’t resist commenting – great info thanks.

Gotchya point, kinda brilliant work you’ve done here ;).